The History of UTCVM

The move to establish a veterinary college in Tennessee really did have a life of its own. As early as 1967, interest was developing, although not yet developed within the university. Instead, agricultural and legislative leaders in the state were discussing it. “They deliberately did not try to contact us,” said former UT president Dr. Ed Boling in a 1993 interview. “Their idea was that ‘we’re going to do this because we think it ought to be done for the state and for the university, whether they want it or not.’ ”

The establishment of a veterinary college was not on any UT wish list. “It was not on our list anywhere,” said Boling. Former UT president Dr. Joe Johnson agreed. “The creation of the veterinary school had a life of its own outside the university through the Farm Bureau and through legislators.” Typically, a new college would involve a lengthy approval process within the state and the university. “It really came out from almost a landslide among the agriculture community to us, to the legislature and to the governor,” said Johnson.

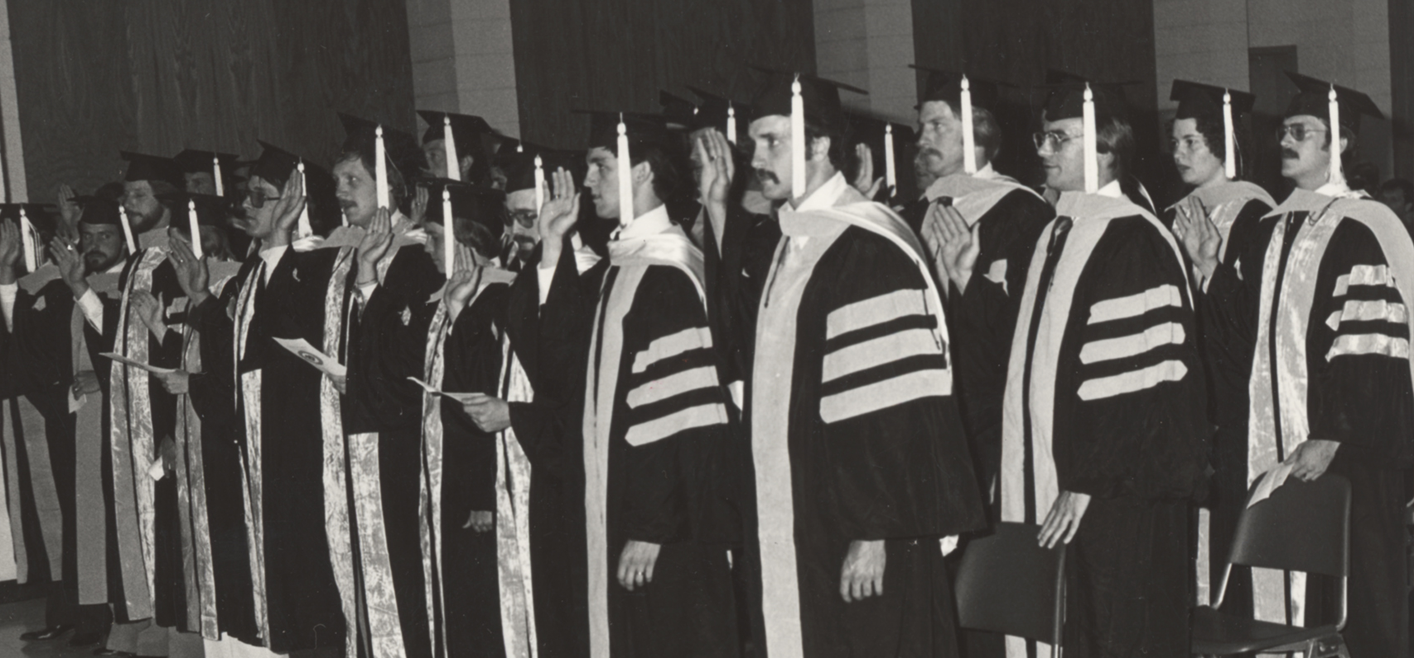

Between 1972 and 1976 a feasibility study was authorized, legislation establishing and funding a veterinary college was passed, a dean and initial faculty were hired, and the Class of 1979 was admitted, all before ground was broken for the new building in 1976.

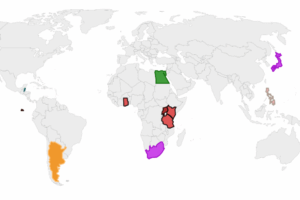

What prompted this groundswell of support in an idea? The first veterinary school in Tennessee actually was the Collins Veterinary College in Nashville, which opened and closed the same year—1899. Before the UT college opened, Tennessee residents made use of contracts that allowed Tennessee students to pay in-state tuition at veterinary schools in other states, primarily Ohio and Alabama (Auburn and Tuskegee). Slots in those contract schools were limited. In 1966, Auburn only had slots for nine Tennessee students. Access to veterinarians was particularly acute in Tennessee’s rural counties, with 30 of the state’s 95 counties having no veterinarians practicing in the mid-1960s. Legislators were concerned, as was the Tennessee Farm Bureau.

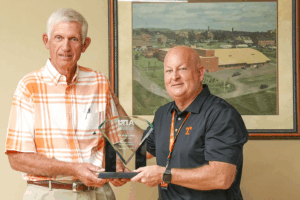

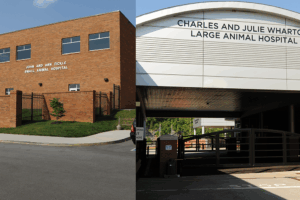

Clyde York worked on his family’s farm in Overton County before attending UT as an agriculture student. He became an extension agent, later Tennessee Farm Bureau president, and a UT Trustee. The suggestion to the UT Board of Trustees to conduct a feasibility study establishing a veterinary school came from York. “If you had to give any one person credit, the lion’s share of credit goes to him,” said Johnson. Years later when the Clyde York Veterinary Medicine Building was dedicated, a surprised York said, “It was a mighty nice thing that happened to me, and I’m highly honored.”

The forces to create a veterinary school also included the Tennessee Veterinary Medical Association, which established a committee in 1967 to review the possibility. Among those on the committee was Dr. George Merriman, a veterinarian who taught pre-veterinary courses in the animal science department. For years Merriman was the sole UT contact for all things veterinary medicine. A vote by the TVMA unanimously supported the establishment of the school. Next, the university contacted the American Association of Veterinary Medicine (AVMA), which provided a list of names of veterinarians with knowledge of developing a veterinary school.

A feasibility committee was established at UT in 1968 to conduct a three-day meeting on the possibility. Agriculture and veterinary deans from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Purdue University, Ohio State University, and the University of California met under the direction of Dr. Webster Pendergrass, then dean of UT’s College of Agriculture and later vice president of UT’s Institute of Agriculture. Kingsport veterinarian Dr. Tyler Young also served on the committee, which had a briefing by Dr. J. B. Jones, then a veterinarian with the UT Memorial Research Center and Hospital. He later became a department head at the UT College of Veterinary Medicine.

The final finding was a veterinary school at UT was indeed feasible, noting that proximity to Oak Ridge, the UT Medical Center, agriculture, and biomedical academic disciplines at UT all contributed to the finding. The final version of the report, however, was not released until 1972. Although there was little apparent progress at UT during the previous four years, that was not the case throughout the Southeast. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia-Maryland, and North Carolina had established or were establishing veterinary schools.

Caution was displayed by the Tennessee Higher Education Commission (THEC), which was discussing with Florida the possibility of a regional plan, with Tennessee veterinary students taking one year of courses in the UT College of Agriculture, followed by two years at Florida’s veterinary college, then a fourth-year clinical clerkship in Tennessee. The THEC executive director was also seeking more contract slots at the University of Georgia for Tennessee veterinary students. A headline in the Chattanooga Times in 1973 “Caution Urged on Veterinary Schools” prompted renewed progress for a Tennessee school. The Tennessee Legislature House Joint Resolution #235 directed THEC to study the feasibility and report back to the legislature by October 1973.

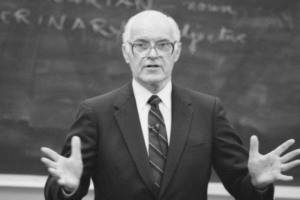

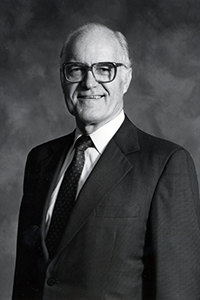

Enter Dr. Willis W. Armistead, who was hired to conduct the study. Armistead was the current dean of Michigan State University’s veterinary school. He was former dean of Texas A&M’s veterinary school, and past president of both the AVMA and the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges. He was the founding editor of the Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, a World War II veteran who served in Italy, and was sought after for academic positions in other universities, including provost and president.

Armistead’s thorough study for THEC, the “Increased Veterinary Services for Tennessee and Consultant’s Report,” issued in November 1973 outlined options to increase the number of veterinarians in Tennessee. At the time, there were 13.5 per capita veterinarians per 100,000 people nationally. In Tennessee, the number was only nine per 100,000. Armistead looked at the availability of increasing contract spaces at other states; he reviewed the possibility of a veterinary school with three potential sizes from 60—100 students to jump-start an increase in numbers of practicing veterinarians. The case was made that establishing the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine was the direction the state and the university should pursue.

Four months later, legislation was introduced and passed less than three months later with only one dissenting vote on Mar. 11, 1974. Nearly everyone wanted to be a sponsor of the legislation. A dilemma developed, however, over the creation of a medical school at East Tennessee State University. Winfield Dunn, then Tennessee governor, had vetoed the ETSU medical school, only to have his veto overturned by the legislature. Dunn, a dentist, supported the veterinary school. His decision to support a veterinary school in East Tennessee, but not a human medical school nearby created political pressure for the governor.

Boling and Johnson described a memorable meeting with the governor in 1974 in which Dunn asked them to withdraw the legislation. Boling said: “Governor, you’re giving us credit for having a lot more power than we have.” Dunn left the room, but later when the bill passed, he supported the veterinary school effort entirely, Boling added.

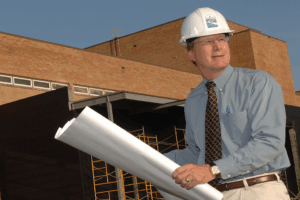

With the legislation passed and funding allocated to start the college and construct the building, a dean was needed. Pendergrass, now vice president of the Institute of Agriculture, went to Boling’s office in 1974 to suggest a founding dean: Armistead. Boling was skeptical that the distinguished Armistead would consider leaving Michigan State to come to Tennessee. But he did. “One of the reasons I came here was that it appears to me that there was such an unusual amount of support for a new program,” said Armistead. The legislature appropriated $17 million to construct the building, establishing the veterinary college as a budgetary line item, in part, said Johnson, to protect it. Armistead began hiring faculty and staff, overseeing the architecture and construction, while also overseeing the process of evaluating student applicants.

The early development of the UT College of Veterinary Medicine had many supporters. Armistead put the vision in motion by hand-selecting faculty, many of whom he had known throughout the country. “He knew professors all over the country who wanted to join him,” said Boling. “It was a good college right from the start.” Joe Johnson concurred. “It did have a life of its own and has been a tremendous success story. It really has.”

Explore More on

CompassionFamily

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE