Can One species help another in a crisis?

The Clinical Need

Over the last few decades, pigs have become established as companion animals, and veterinarians are treating more senior swine than ever before. With advanced age comes the increased risk of anemia, a dangerous reduction in the circulating blood volume and red blood cells that can occur during surgery or illness for pathologies like cancer. The gold standard for the treatment of severe anemia in all species is a blood transfusion. In a pinch, where do you find compatible pig blood? Unlike dogs or cats, there is no established standard for pig blood donation, making it hard for veterinarians to find compatible pig donors quickly, especially in emergencies.

Searching for a Solution

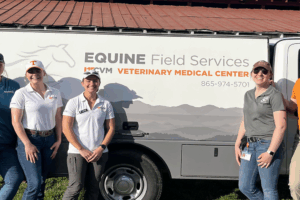

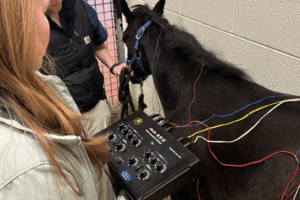

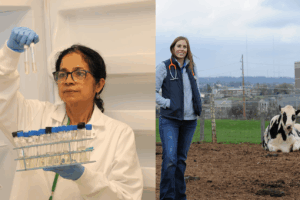

Veterinarians who treat pigs often struggle to find species-specific blood products. This lack of access to pig donors or pre-made blood bags can delay treatment or lead to life-threatening outcomes. “We need practical options for administration of blood to pigs inside and outside of the operating room, as this really can make a great difference in outcome,” said Chiara Hampton, UTCVM assistant professor of anesthesia. Hampton and her team, including Victoria Diaz (CVM ’25), set out to explore xenotransfusion: the transfer of blood from one species to another. This study explored whether blood from cows (bovine) or dogs (canine) could be safely used for pigs, at least in one-time emergency situations. Diaz worked on this study during the summer of 2023 under a research scholarship at the veterinary college.

Promising Discovery

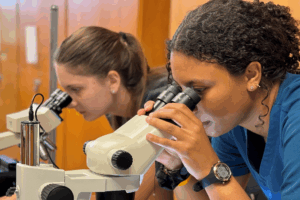

In a laboratory setting, the team tested how pig blood reacted with cow and dog blood. The results were as surprising as they were promising: Bovine blood was mostly compatible with pig blood, opening up the potential for life-saving transfusions when time or resources are scarce. Cows, thanks to their large size and gentle nature, make ideal donors in these situations. However, canine blood caused severe reactions in laboratory tests and was found to be unsafe for pigs. The team also compared two ways of checking compatibility: the traditional hour-long saline method and a quicker slide test. While tempting in emergencies, the rapid slide test missed key problems such as hemolysis, the breakdown of red blood cells, which can cause serious reactions in the recipient, so it isn’t recommended for emergency screening.

For veterinarians and pig owners, these findings are a beacon of hope and caution. “Not only did we find blood that could be compatible for transfusion to pigs, but we also found blood that is absolutely contraindicated, which means that we have already saved lives by showing what is not a safe option,” said Hampton. The study’s message is clear: Cow blood could save lives when pig donors aren’t available, but dog blood must never be used.

The findings also stress the need for standard testing methods before any transfusion, as shortcuts may not be a safe option. This study represents the first step in learning if blood xenotransfusion to pigs can lead to better emergency care and improve outcomes in both pet and livestock pigs, particularly where pig donors are unavailable.

View the full scientific article

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE