Preparing Practice-Ready Veterinarians

“I’m making prostates today!”

This exclamation came from veterinary technician Renee Crane in a recent Academic and Student Affairs staff meeting. Crane was sharing what she was working on in her role as one of the creative minds in the college’s Simulation Laboratory.

“Oooh! What kind?!” a colleague asked. The answer: Specifically, a dog model for students to learn how to perform rectal exams to palpate the prostate.

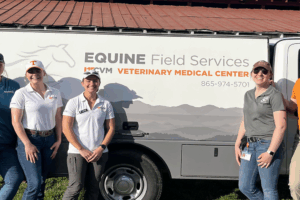

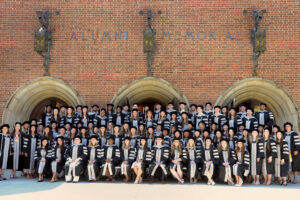

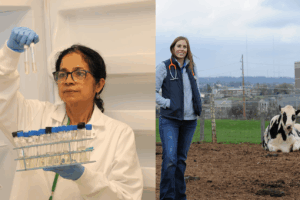

This kind of excitement for creating practice-ready veterinarians permeates the college, from its academic affairs support staff to its faculty and college leadership and everyone in between. Around 75 percent of our graduates go straight into private practice. So, our main goal is to prepare students to use their scientific knowledge, skills, and professionalism to be able to provide animal health care, independently, at the time of graduation. We constantly seek input from various stakeholders and stay up to date with veterinary education research to determine whether we are meeting this goal. We use that input and knowledge to adjust the curriculum.

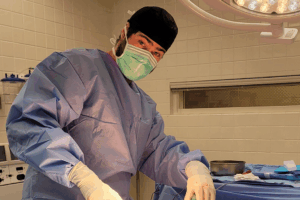

Several years ago, our alumni and their employers were sharing that our program needed more opportunities for students to practice small-animal dentistry and basic surgery skills. Now, all students complete a dentistry course, and an elective dentistry course and clinical rotation have been added. Likewise, a high-volume, spay and neuter elective rotation became a requirement during the clinical curriculum, and several new pre-clinical electives in both small- and large-animal surgery are being offered to provide students with more hands-on experience.

“Our students and graduates not only provide high-quality patient care but also embody a commitment to integrity”

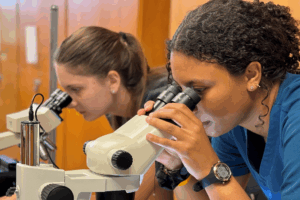

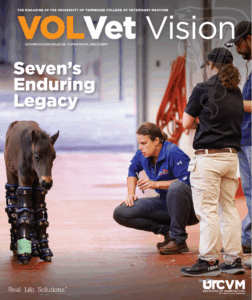

In the Simulation Lab, which opened in its new space in 2023, learners practice their recently acquired skills in an environment where they can gradually build their confidence, unrushed and with feedback. A video software program enables students to record themselves performing certain simulated procedures independently without the stress of an expert peering over their shoulders. The expert can watch the recording and assess their performance later. Simulated models are being integrated throughout the pre-clinical curriculum to prepare students for clinical training, too.

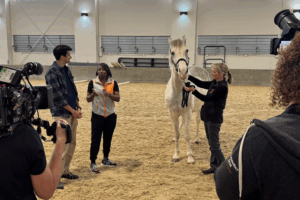

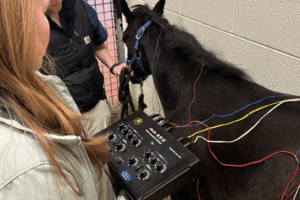

In 2024, a clinical applications and integrations (CA&I) course series was launched to enable learners to integrate and apply what they learn in basic science and systems-based classroom courses. This five-course series expands upon components of other courses during the same semester. For example, while students are enrolled in the Oncology course, they are learning to palpate, measure, and map lymph nodes in the CA&I course. To help students practice fine needle aspiration, veterinary technician supervisor Jimmy Hayes uses cherry tomatoes. During the spay and neuter elective, learners first brush up on their suturing skills with silicone skin pads, move to performing a spay on an abdominal model, and finally complete an anesthesia scenario using a SynDaver dog and an iSimulate monitor. A horse head model is available to practice nasogastric intubation, a critical procedure used to diagnose and treat colic.

Throughout a sixteen-month clinical training program, clinical instructors evaluate students on all nine clinical competencies outlined by the American Veterinary Medical Association. Many years ago, we added a tenth competency: professionalism. We expect our students and graduates to not only provide high-quality patient care but also to embody a commitment to integrity, empathy, and advancing the practice of veterinary medicine.

We ask students, as they prepare to graduate, how prepared they feel to meet their first-year goals. Once they’ve been in their careers for around nine months, we ask their employers how well prepared our alumni were, and at eighteen months, we again ask our alums how well we prepared them. Consistently, the numbers tell us that graduating students rate their own preparedness level lower than do their employers. As alums, graduate perception of preparation tends to increase slightly. This trend suggests a natural anxiety of graduates who will soon be independent practitioners, recognition by their employers that new graduates are still learning, and reflection by alums that perhaps some of that initial anxiety was misplaced.

Over the last ten years, the average pass rate for Tennessee students on the North American Veterinary Licensing Exam is 97 percent. But success is not measured by numbers alone. We are also proud to say that we graduate veterinarians who consistently tell us they are satisfied with their choice to become a veterinarian.

Want to support the Simulation Laboratory Fund? Call 865-974-8140

Explore More on

CompassionKnowledge

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE